Native Plants and Wildlife Gardens is devoted to discussing the value of native plants in our landscapes, wildlife gardening, ecological restoration, schoolyard habitats, green roofs, and other means of creating healthy gardens for a healthy planet. (Carole Sevilla Brown)

This past summer, it was with heavy heart I said goodbye to another green space in Toronto – The Back Campus field at the University of Toronto, where I studied and now work. It was a pastoral setting amongst heritage buildings and old English elms. It was an integral part of the university commons.

Previously, during 1992-94, a plan was pursued to have underground parking with an artificial field on top, but it was ultimately stopped.

Then, the push for the Pan Am Games 2015 led to a proposal to pave and then artificially turf the historic back campus to build two international field hockey pitches. (Note: there are only 25 field hockey players currently at the institution).

In a flagrant lack of transparency, an ill-informed Governing Council used in-camera proceedings and never disclosed its actions until a contract had been signed to proceed with the paving.

The desecration of a major portion of its campus – to close off a university common and destroy green space in the heart of Toronto generated a serious backlash which resulted in a last ditch effort – a proposal through city council to designate the green space as a cultural heritage landscape. But to no avail – it was a done deal, even though an alternative venue was available with the newly constructed pitches in Brampton, northwest of the city. Since the Pan Am Games will be hosted in various locations throughout the Greater Toronto Area, it made perfect sense.

If the field was accused of being in bad shape, it was because it was not maintained well at all. And to add insult to injury, every winter maintenance personnel used to store snow removed from nearby roadways. As it melted in the spring tons of garbage would be revealed and included toxic waste, such as cigarette butts along with oily residues and salt. No wonder the field was never in good condition.

So while I was preoccupied with the goings-on at the university campus, two other projects were flying under the radar near my home.

My local primary school and community centre had just undergone a building expansion. They had converted a small play area that was mulched into a crumb rubber surface with low climbing ropes. What I hadn’t realized was something far more sinister was afoot – the imminent conversion of natural turf/mulch to a synthetic field.

Apparently, the local school board (TDSB) gave the parents or a select group of parents two choices for the surface of their playground: dirt or turf (artificial). They tried once to re-sod the field and it didn’t survive the foot traffic. Hence, the campaign for “Dirt to Turf” was born. The community was not consulted extensively. Many, like me did not dream that they were referring to artificial turf and not natural turf.

TDSB did not have its own funds to help the project. In fact, TDSB is notorious for selling off “surplus” school lands to fund their board because they cannot carry a deficit (otherwise the province steps in and makes cuts to programs). They are letting green space go to condominiums when they might need it for future expansion in enrolment. Yet, they are squandering on things like installing pencil sharpeners for $143 a pop!

The major funding was secured through Section 37 monies, a community development fund fed by concessions given to developers seeking additional amenities in contradiction of the planning department’s mandate. As well, some parents and local businesses raised funds.

An elaborate pamphlet showed up in my mailbox with before and after pictures of the field with fundraising sponsorship levels and a diagram and description of the design. The “after” picture showed artificial turf surrounding tree trunks, but the diagram revealed a fairly generous mulching area around the trees (little solace to those who wanted to keep it natural).

A couple of local highschools have succumbed to the sell-off-land-for-condos scheme and converted to synthetic fields. Two other primary schools nearby had already been infected by the artificial turf syndrome: Sunnybrook School, private, and the public Bessborough Drive Elementary and Middle School in nearby Leaside.

Some opt for the front (above), while others like Bessborough School hide it in the back.

Signage: Private Property! Since when is public school, private property? Please respect our artificial turf (they didn’t respect the sign…)

Two neighbours just north of me shared a contractor to do some backyard work. One installed a large shed, fire pit and pavers. The other installed a children’s playset.

My immediate neighbour invited me to take a look over their fence to check out the kid’s playground.

Something didn’t look right, so I stuck my hand between the fence slats and confirmed my worse suspicions – fake lawn! I had never experienced it on a private residential level.

There it was barely contained, just on the other side of the fence – artificial turf peaking through fence. I reached in to and tugged on it, but it was firmly glued down.

The large white oak (Quercus alba) has a commanding presence with a dbh of at least 90 cm (36+”). I’m not sure how much soil was extracted, tree roots disturbed and aggregate laid on top as a base during the construction. I would hazard a guess that the plastic turf is glued down right up to the base of the tree.

It would be a shame to lose a tree that provides all the ecosystem benefits of a large, mature tree and native plant: oxygen, shade, air filter, nesting sites and acorns for squirrels, habitat for invertebrates and thus food for birds.

A very disturbing trend has emerged in Toronto with the installation of artificial turf at teaching institutions and even at the residential yard level and with the subsequent loss of green space. I’m not a fan of lawn, but it does have some utility in pathways through gardens and in sports applications. And it is definitely the lesser of two evils.

Make no mistake – artificial surfaces are not green spaces. I’ll tell you why:

- by definition, an artificial surface is not natural and does not undertake evapotranspiration (cooling effect) as would a natural system; it is equivalent to pavement

- negative impact on surrounding trees during excavation

- negative heat island effect

- watering and storm sewer runoff with leachate from the petroleum product (synthetic turf) plus any biocides or algaecides to deter bacterial or algal growth or solvents to remove gum, paint, etc.

- increased injuries – the sports fields of public schools are very hard (no rubber crumb layer which while more toxic, allows for softer landings)

- heightened restrictions imposed on the use of the field and the time of use by the community (exclusionary, additional permit fees?)

- unsustainable – short lifespan and replacement of artificial surface within 8-12 yrs. and base in about 20 yrs. (landfill or recycle worn out turf?)

Aggregate layers allow permeability but…perforated collection pipes connect to existing storm pipes to capture and accelerate controlled field drainage. Storm water runoff from synthetic turf with its toxic leachate is transported to the sewer system storm and goes straight to the lake, untreated. And since antimicrobial treatment is standard practice on artificial turf fields, it also goes straight to the lake, untreated. In the past, school children have painted yellow fish beside storm sewer grates to remind residents not to dump anything down the grate or wash their car in the driveway in such a way that allows effluent to go to the curb and drain into the storm sewer system (it is a bylaw offence in Toronto to dump anything in the storm drains, unless it is approved larvicide under the mosquito abatement program of controlling West Nile Virus). Soap, biodegradable or not, can strip the protective mucous layer from fish. Antimicrobial agents can’t be a good thing for rivers and streams, either.

And then there’s the problem of whether toxic compounds from crumb rubber could be released into air or water. At Varsity Stadium when the synthetic turf layer was being installed, tiny blue balls of rubber were blowing around all over the sidewalk and settling in the grassy plots of trees, outside the stadium. If the crumb rubber was made from recycled tires, it would be of variable quality and variable toxicity being spread about.

The ‘heat island’ refers to urban air and surface temperatures that are higher than those of nearby rural areas. Built up areas have more paved over surfaces which absorb heat during the day and release it at night.

Elevated temperatures from urban heat islands, particularly during the summer, can affect a community’s environment and quality of life. While some impacts may be beneficial, such as lengthening the plant-growing season, the majority of them are negative.

These impacts include:

- increased energy consumption (increased demand for cooling = air conditioners)

- elevated emissions of air pollutants and greenhouse gases (climate change buddies)

- compromised human health and comfort by contributing to general discomfort, respiratory difficulties, heat cramps and exhaustion, non-fatal heat stroke, and heat-related mortality. Heat islands can also exacerbate the impact of heat waves

- impaired water quality (heated stormwater generally becomes runoff, which drains into storm sewers and raises water temperatures as it is released into streams, rivers, ponds, and lakes, threatening aquatic life. (According to the US EPA)

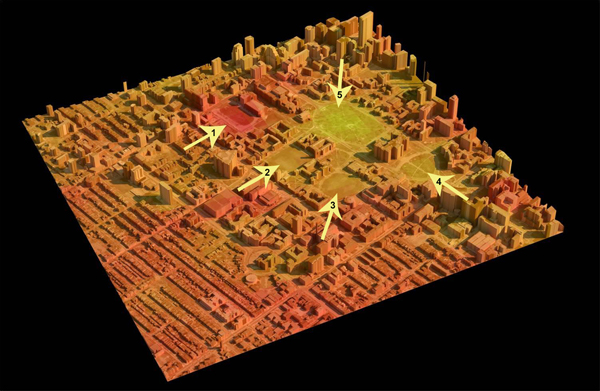

One way to identify hot spots is by taking a snapshot of infrared radiation or the heat energy emitted from a material.

Key:

(1) U of T, Varsity Stadium (former site also hosted concerts, including the infamous John Lennon & Plastic Ono Band on September 13, 1969)

(2) U of T, Back Campus (now under conversion to an artificial field). My workplace is beneath Arrow 2.

(3) U of T, King’s College Circle – natural turf; site for intramural sports and pathway for the graduate migration across to Convocation Hall to receive their degrees.

(4) Front lawn of the Ontario Legislative Building

(5) Queen’s Park (arboretum and squirrel sanctuary)

“The worst offender for heat island effects in the downtown area of the campus was the conversion of Varsity stadium to artificial turf and the track . . . There is a direct correlation with the urban surfaces that are living and cooling effects during heat events. Evapo-transpiration cools the surfaces and mitigates urban heat island effect.

Not enough people on campus have considered the impact of artificial turf on heat impacts . . . We were shocked when we made the first image and then traced the change to the dates of construction. Who would have thought that nice “green looking” varsity open space would be the hottest area?

(Referring to Back Campus conversion to artificial surface). There seems to be no reference in the proposal to an assessment of the heat impacts of converting such a large surface area from a living surface to an artificial surface. If this were a building it would be required to have a green roof and a parking lot would be required to compensate with tree canopy as I understand they were asked to do with the parking lots for the Pan Am Scarborough site as part of the Toronto Green Standards.” (John Danahy, Centre for Landscape Research in the Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design).

Stuart Gaffin, an associate research scientist at the Center for Climate Systems Research at Columbia University, initially became involved with the temperature issues of synthetic turf fields while conducting studies for another project on the cooling benefits of urban trees and parks. Using thermal satellite images and geographic information systems, Gaffin noticed that a number of the hottest spots in the city turned out to be synthetic turf fields. He measured the temperatures of different surfaces to illustrate the point: air/water = 94 F (34.4C); Bermuda grass = 104 F (40C); sand = 132 F (55.6C); asphalt = 136 F (57.8C); synthetic turf = 165 F (73.9C).

There isn’t much you can do if you go the route of synthetic. The only thing you can do is irrigate, including wetting down the surface area when it’s hot. The irrigation requirement for elite sports turf is higher than that for premier or local sports turf (typical schoolyard). And then you have that pesky problem of storm sewer runoff with leachates.

For natural turf, depending on location, the irrigation requirement for cool season grasses is higher than that for warm season grasses.

Meanwhile….

A few articles have appeared in the local papers about pro sports returning to their roots…as in natural grass roots. BMO soccer field converted back to natural. Skydome (now Rogers Centre) is looking to replace their artificial turf with grass for the local baseball team, Toronto Blue Jays by 2018.

If pro sports are heading back to natural turf and amateur sports (highschool, primary school) are heading in the opposite direction, then schools should be side-lined until they come to their senses. This is the antithesis of what a schoolyard should be. They should be more involved with “greening” schoolyards, e.g., School Habitat Garden in Illinois Prairie Country.

“Installing natural grass instead of artificial turf can save the school in excess of $1,460,000 over 20 years, money that could be spent on other projects or programs.” Source: The Truth about Artificial Turf

Monsanto chemists invented AstroTurf in 1964 and initially called it “chemgrass”. Its original purpose was to replace natural grass that had difficulty growing in indoor stadiums. The Houston Astrodome was the world’s first fully enclosed stadium with a synthetic turf field. Synthetic turf was designed for both portable and permanent use either indoors or outdoors. Base construction can be concrete, crushed stone, infill layers of crumb rubber, or asphalt.

A good synopsis on the history of turf – Synthetic Turf: Health Debate Takes Root.

The Truth about Artificial Turf – pros and cons of natural vs artificial turf.

The ongoing deconstruction of the natural field to synthetic at Back Campus field, U of T.

Keeping Back Campus Green Facebook page devoted to keeping the Back Campus Green and now to holding the memory of restoring it after 2023, when the item is revisited at City Council.

Alarm raised about Toronto looking like a set from Teletubbies.

When community residents were promised field access, but then there were the permit fees.

Originally published December 26, 2013 on Native Plants and Wildlife Gardens